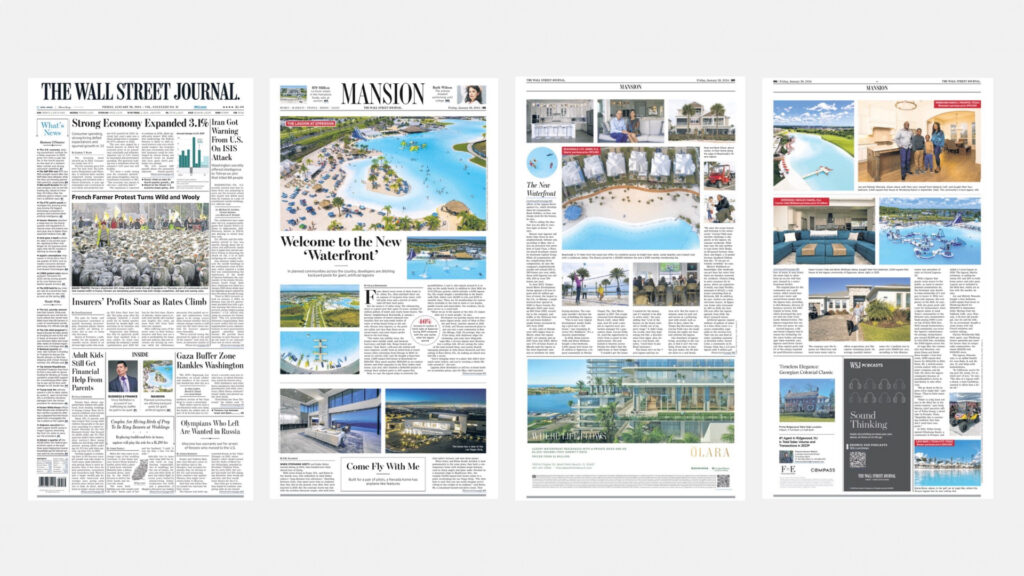

In planned communities across the country, developers are ditching backyard pools for giant, artificial lagoons

From almost every room of their home in St. Johns, Fla., Neal and Barb Shact see an expanse of turquoise blue water, with tall palm trees and a stretch of white sand off their back patio.

But the ocean is 17 miles away. The shimmering shore is a giant pool that spans 14 acres, contains 37 million gallons of water and courts home buyers. The Shacts’ neighborhood, Beachwalk, is among a growing number of master-planned communities that use man-made bodies of water to bring beach living to the suburbs. Houses near lagoons, as the pools are called, cost less than those on an actual beach, and some buyers prefer them to the real thing.

View from above of the Shacts’ West Indies-style waterfront home.

PHOTO: ADAM T. DEEN FOR THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

“The water was awfully close, the houses were awfully small, and between hurricanes and high tide, things looked precarious,” Neal Shact, a 69-year-old retired software engineer, recalls from an initial look at beach houses when relocating from Chicago in 2020. Instead, he and his wife, now 56, bought a three-bedroom, 2,600-square-foot house at Beachwalk for $911,000. They spent another $100,000 on an outdoor shower and other upgrades to the West Indies-style house. Last year, they finished a $100,000 project to enlarge their outdoor patio to 450 square feet.

Now, he says the lagoon helps to entertain the grandchildren, 2 and 4, who splash around in it or play on the sandy beach. In addition to their HOA fee of $1,234 per quarter, which includes a $400 lagoon fee, the couple bought a membership in the Beachwalk Club, which costs $5,000 to join and $305 in monthly dues. There are 50 memberships for nonresidents available at the club to swim or use kayaks, paddle boards and waterslides. For residents, the lagoon serves as a social hub.

Neal and Barb Shact at their home at Beachwalk. In 2023, the couple finished a $100,000 project to enlarge their outdoor space.

PHOTO: ADAM T. DEEN FOR THE WALL STREET JOURNAL (4)

“When we go to the lagoon or the club, it’s impossible not to meet people,” he says.

Developers are pouring money into enormous lagoon pools, most of them in Florida and Texas. Another opened in 2021 in Utah, and

Disney announced plans to put one into a new community in Rancho Mirage, Calif. On average, they are 8-feet deep, with shallower edges for swimming, and some have lifeguards. Lago Mar, a 12-acre lagoon near Houston, has a sailing club. All are raising the value of the land around them, says Lesley Deutch, managing principal at John Burns Research and Consulting in Boca Raton, Fla., by making an inland area feel like a resort.

The Shacts’ house overlooks a 14-acre lagoon. Their grandchildren play on the sandy beach behind their house.

“You’re bringing water to a place that didn’t have much water before, and you’re creating a whole lifestyle around it,” she says.

Lagoons allow developers to sell lots to home builders at premium prices, says Uri Man, chief executive officer of The Lagoon Development Company, which develops them for communities. Home builders, in turn, can charge more for the houses, he says.

“We’re selling the idea that you are able to vacation right at home,” he says.

The 12-acre lagoon at Lago Mar, a community of 4,000 houses in the Texas City area, near Houston. Residents and guests can swim, sail, kayak and paddleboard on the lagoon.

PHOTO: LAGOON DEVELOPMENT

Houses near lagoons sell faster than those in new neighborhoods without one, according to Man, who is also an executive vice president at Land Tejas, a Houston-based developer owned by Starwood Capital Group. While all communities differ, complicating direct comparisons, he says the company’s neighborhoods usually sell around 200 to 300 homes per year, while those with lagoons can sell 400, 500 or even 700 homes per year.

In June 2023, Tampa-based Metro Development Group opened a 15-acre lagoon with 35 million gallons of water, the largest in the U.S., at Mirada, a neighborhood that opened in 2020 in Pasco County, Fla. Mirada’s 2023 sales were up 89% from 2022, according to the company, and traffic to the Welcome Center and home builders’ model homes increased by 40% from 2022.

A splash playground in the amenity village at Lago Mar.

PHOTO: LAGOON DEVELOPMENT

In July, sales at Mirada were 121% higher than in March, when the lagoon hadn’t yet opened, and 153% up from July 2022. Metro says 47% of home buyers at Mirada rank the lagoon as the most important amenity or attribute for their buying decision. The company wouldn’t disclose the cost of building the lagoon.

“This is not your typical development model, building a pool and a clubhouse,” says managing director Eric Wahlbeck. “It’s a massive undertaking.”

Dawn Curran-Tubb and Brian Wildman use a golf cart to get around Epperson, a lagoon community in Wesley Chapel, Fla., where they bought a four-bedroom house in 2021.

PHOTO: MICHAEL GRANT FOR THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

In 2021, Dawn Curran-Tubb and Brian Wildman bought afour-bedroom, 3,500-square-foot house for $1 million at Epperson, a lagoon community in Wesley Chapel, Fla., that Metro opened in 2017. The couple relocated from Huntington Beach, Calif., when Wildman, now 53, took a new job as regional asset protection manager for a gas-station chain. Curran-Tubb, 54, used the opportunity to retire from a career in law enforcement. The pair looked at beaches across Florida but didn’t find the right home at their budget.

“I couldn’t get the house I wanted for the money, and if I wanted to be able to retire early,” she says, adding that “a lot of the houses on the beach were old or totally out of my price range.” It didn’t help, she recalls, that they kept seeing red tide, a discoloration from algae. Also, living on a real beach, she notes, “you’d have to pay flood insurance.”

The water-based amenities at Epperson, where prices of new homes range from the $300,000s to over $1 million, include an inflatable, 30-foot water slide and other water toys.

PHOTOS: TYLER JOHNSTON/COLE MEDIA PRODUCTIONS (2)

The house isn’t on the 7-acre lagoon and has no view of it. But the water is minutes away by golf cart and serves as a gathering spot with events such as Beer & Bucs, when the Tampa Bay Buccaneers play. Curran-Tubb says she made friends she might not have met without the lagoon.

One drawback of lagoon living, according to the couple: It isn’t the real thing. From time to time, the pair makes the 40-minute drive to a real beach. “We miss the ocean breeze and listening to the waves crash,” Curran-Tubb says. Another challenge is day guests. On summer weekends, Wildman says the pair prefers to stay home with Shady, an 80-pound German shepherd, and Bagel, a 14-pound German shepherd-Chihuahua mix. “It can get extremely crowded,” he says.

Metro’s Wahlbeck acknowledges that weekends can get busy but notes that there are beaches reserved for residents. Visitors bring in extra revenues for lagoons, which are expensive to build, says Karl Pischke, principal at RCLCO, a real-estate consulting firm in Bethesda, Md. In addition, he says, visitors are potential home buyers. At Epperson, home sales increased by 46% in 2019, the first full year after the lagoon opened, from 2018, the firm’s research shows.

Curran-Tubb and Wildman with Shady, a German shepherd, and Bagel, a German shepherd-Chihuahua mix, outside their 3,500-square-foot house at Epperson.

PHOTO: MICHAEL GRANT FOR THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

The living room in Curran-Tubb and Wildman’s $1 million home.

PHOTO: MICHAEL GRANT FOR THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

Artificial lagoons require millions of gallons of water at a time when water is a scarce commodity, especially in the western U.S. They can use any kind of water, including seawater or brackish water. Desert Color, a community in St. George, Utah, has a 2.5-acre lagoon with 4 million gallons of water. It uses brackish water high in saline from an on-site well that gets cleaned by a water-treatment facility. The original plan for the community was a golf course, which would have used more water and served fewer people than the lagoon does, according to Rob Behunin, director of business services for GWC Capital in Orem, Utah, which developed the project with the Utah Trust Lands Administration. The lagoon evaporates less water than turf grass, he says.

Crystal Lagoons, a Miami-based company that licenses the technology for the water bodies and manages them remotely, says lagoons need fewer chemicals than regular pools and 2% of the energy required for pool-filtration systems. The company says the lagoons are filled once and need more water only to offset evaporation, just like regular swimming pools. On average, monthly maintenance for a medium-size lagoon costs $9,600 per acre, according to Iván Manzur, senior vice president of sales at Crystal Lagoons US Corp.

Curran-Tubb and Wildman were drawn to the millwork and crown molding inside the house.

PHOTO: MICHAEL GRANT FOR THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

With a lagoon that grants some access to the public, as many in master-planned communities do, the developer may decide to keep ownership of it and pay to insure it. With resident-only lagoons, the cost passes to the HOA, he says.

Still, the giant pools add costs for homeowners. Once a lagoon opens at Land Tejas’s communities in the Houston area, homeowners begin paying $400 a year on top of their HOA fees. With enough homeowners, each community can cover the lagoon’s maintenance. On average, homeowners pay around $1,200 per year in total HOA fees, including the $400 lagoon access fee.

Lago Mar homeowner Diana Boise in her golf cart.

PHOTO: DIANA BOISE

At Lago Mar, the community near Houston, residents Diana and David Boise bought a four-bedroom 1,900-square-foot house for $244,000 in 2021. Boise, 80, a retired senior system analyst with a computer company, and his wife, 69, chose the lagoon community because of granddaughters Avery, 8, and Kinley, 6, who often visit.

“We go down to the lagoon every single day,” says Diana. “They’re little water babies.”

“Water is a big issue not just in the West but in the entire country,” says Craig Martin, chief executive officer of Tellus Group, a developer in Prosper, Texas. “Hopefully this is convincing residents that they don’t need their own pools.”

In 2014, Tellus Group opened Windsong Ranch, a community in Prosper, and added a 5-acre lagoon in 2019. The lagoon, Martin estimates, is adding between 10% and 20% to both home prices and sales pace. Lagoon use is included in the HOA fees, which are in line with the market, he says.

Melody and Joe Wanzala with their sons Akena, 12, and Raila, 8, in front of their four-bedroom, 3,400-square-foot house at Windsong Ranch, a lagoon community in Prosper, Texas.

PHOTO: THE CHRISSY WEATHERSBY BALL GROUP

The 5-acre lagoon at Windsong Ranch, north of Dallas.

PHOTO: TELLUS GROUP

Joe and Melody Wanzala bought a four-bedroom, 3,400-square-foot house at Windsong Ranch for $910,000 in September 2022. Moving from the Oakland, Calif., area, Wanzala, a 54-year-old paralegal, says he and his wife, 43, an accountant, bought a stone house with tall French windows and vaulted ceilings.

Chrissy Weathersby Ball, their agent, says Windsong buyers generally pay more for houses than at comparable communities—between $50,000 and $100,000 more. The lagoon, Wanzala says, is an added benefit for sons Raila, 8, and Akena, 12, and helps with homesickness.

“In California, you’re living near the ocean. It’s so much part of you,” he says. “The idea of a lagoon with a beach, a mini-Caribbean, seemed to offset that a little bit.”

Contact Us

Want to know more about the meeting point of the 21st century?

We do not sell entrance tickets or properties; please contact the project directly.